Most of us take for granted the twenty-seven books that make up the New Testament, but this was not always the case. It was not uncommon in the ancient world for there to be different books included in Christian collections of writings. Such works as the Letters of Clement, Epistle of Barnabas, and Shepherd of Hermas are included in such noteworthy and important manuscripts as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus. For many years the Eastern and Western Churches debated both the inclusion of Hebrews and Revelation. As recently as the 16th century and the Protestant Reformation, there were serious doubts about the works to be included in the New Testament. Of these, Martin Luther’s objections to Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Apocalypse of John (Revelation) were so severe that he placed them in an addendum to his German New Testament. Some contemporary Christian Churches in the ancient parts of the world (mostly the Middle East) still have New Testament canons that differ from the standard twenty-seven book canon of the “Orthodox” (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant). Obviously several factors had to influence why certain writings were included in the New Testament. But what were they?

Most of us take for granted the twenty-seven books that make up the New Testament, but this was not always the case. It was not uncommon in the ancient world for there to be different books included in Christian collections of writings. Such works as the Letters of Clement, Epistle of Barnabas, and Shepherd of Hermas are included in such noteworthy and important manuscripts as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus. For many years the Eastern and Western Churches debated both the inclusion of Hebrews and Revelation. As recently as the 16th century and the Protestant Reformation, there were serious doubts about the works to be included in the New Testament. Of these, Martin Luther’s objections to Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Apocalypse of John (Revelation) were so severe that he placed them in an addendum to his German New Testament. Some contemporary Christian Churches in the ancient parts of the world (mostly the Middle East) still have New Testament canons that differ from the standard twenty-seven book canon of the “Orthodox” (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant). Obviously several factors had to influence why certain writings were included in the New Testament. But what were they?

Since the process of “formal canonization” has remained so fluid (as noted in yesterday’s post), there exists no authoritative list of reasons for why a certain writing was included in the New Testament canon or why one was excluded. However, scholars have suggested a number of reasons for why certain books were included in the New Testament canon.

Since the process of “formal canonization” has remained so fluid (as noted in yesterday’s post), there exists no authoritative list of reasons for why a certain writing was included in the New Testament canon or why one was excluded. However, scholars have suggested a number of reasons for why certain books were included in the New Testament canon.

Antiquity. This means that the writing was considered ancient in origin. The writer of the Muratorian Canon, for example, rejected the Shepherd of Hermas because he believed it had been written recently.

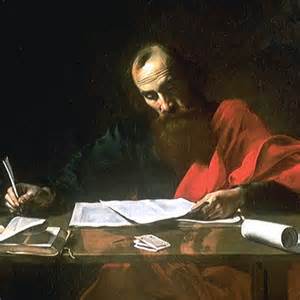

Apostolicity. This criteria meant that only writings attributed to the Apostles or their associates should be accepted. For example, the Gospels of Matthew and John were attributed to the apostles by those names. Papias (in the second century) suggests that Mark was the secretary of the Apostle Peter, and it has long been understood that Luke was a companion of the Apostle Paul. Thus, those four writings were accepted while writings such as the Gospel of Truth were not.

Practical Matters. Simply put, a church had to have a text in order to be able to use it and that text needed to address issues relevant to the church in order for them to accept it. The Epistle of James, for example, was not textually available during the first few centuries of its existence, leading to its “questioned” status in many churches. Further, we may never know what was in Paul’s letter to the Laodicians, but it seems safe to assume that the issues he addressed did not persist in the church very long. On that note, it may be that such letters were the most immediately effective.

Use. The use of the writing was ultimately the most important factor for its being included in the New Testament canon. A writing that was used by earlier Christians and had a place in circulating collections was clearly a writing that was used enough to be considered part of the canon. The Shepherd of Hermas for example, while frequently used in the early years of the church, eventually left circulation and was in fact ‘lost’ for a number of years. Similarly, the widespread use of a writing lead to its rapid acceptance. For example, the writings of the early Church Fathers make it clear that the Gospel of Matthew was available throughout the Roman Empire from at least the second century onward.

Rule of Faith. The most important factor for a writings’ inclusion in the New Testament canon was essentially a combination of the ‘Practical Matters’ and ‘Use’ categories mentioned above, namely, the writings compatibility with the Rule of Faith lived by the Christians receiving any given writing. The Bible is the Book of the Church, and the writings included in the New Testament canon are those that conformed to the lived faith and practice of followers of Jesus. The earliest Christians did not have a Bible, a New Testament, the Four Gospels, or often times any written texts at all. What they did have was a living faith in Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah, the christos. And the writings that conformed to and strengthened that belief were those that were accepted and eventually canonized. Only writings that conveyed the message of Jesus as having come, died, risen, and coming again were those accepted by the Great Church and eventually included in the New Testament canon. Thus it can truly be said that the faith of the church gave rise to the New Testament canon.

Rule of Faith. The most important factor for a writings’ inclusion in the New Testament canon was essentially a combination of the ‘Practical Matters’ and ‘Use’ categories mentioned above, namely, the writings compatibility with the Rule of Faith lived by the Christians receiving any given writing. The Bible is the Book of the Church, and the writings included in the New Testament canon are those that conformed to the lived faith and practice of followers of Jesus. The earliest Christians did not have a Bible, a New Testament, the Four Gospels, or often times any written texts at all. What they did have was a living faith in Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah, the christos. And the writings that conformed to and strengthened that belief were those that were accepted and eventually canonized. Only writings that conveyed the message of Jesus as having come, died, risen, and coming again were those accepted by the Great Church and eventually included in the New Testament canon. Thus it can truly be said that the faith of the church gave rise to the New Testament canon.

To summarize: Where did we get the New Testament? Through the collection and listing of accepted Christian writings. And why are these specific books accepted and included in the New Testament? Because they conform to and strengthen the Christian “Canon of Faith,” that Christ has died, is Risen, and will come again.

Leave a comment